From Paris to Camberwell: How Australia fell in love with Dada

- Andrew McIlroy

- Apr 8, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 23, 2023

‘Dada is a rebellious, playful state of mind’ (Tristan Tzara, 1922)

Now woven into Melbourne folklore, a young Barry Humphries’ breakfast delivery to himself on the way to school is a spot of suburban theatre that warmly resonates decades later.

Humphries instructed his friends to stand at specific points on the platform, ready for his train to pull in. As the doors opened, each would then pass him a certain part of his breakfast. At stop one, he was passed a teacup. Stop two, he would be poured the cup of tea. Stop three, he would be passed a plate; at four, a piece of toast; at five, butter; six, jam and so on. So, when he arrived at the final stop, he had consumed a complete breakfast.

This ‘progressive breakfast‘ may have inspired Humphries to create screen prints of Willie Weeties, in yellow, pink and purple, a three-course visual feast.[i]

Post-war Melbourne seems a distant memory, but Humphries humorous response to mid-20th Century Australia tells us a lot about the lives of the people that inhabited Australia at that particular time.

Melbourne's Camberwell Railway Station

Humphries satirical theatre highlights the resilience of a tradition among artists, writers and intellectuals who beginning in the aftermath of World War I opposed war and its profound consequences. Seen as a short-lived reaction to industrialisation and modernism (a break from the past and a concurrent search for new forms of artistic expression and experimentation), Dadaism in all its subversive glory still resonates in today's chaotic world.

The origins of Dadaism

During World War I, numerous artists, writers, and intellectuals who opposed the war fled to Switzerland. Zurich, in particular, became a hub for people in exile, and it was here that Hugo Ball and Emmy Hemmings opened the Cabaret Voltaire in February 1916.

The Cabaret was a meeting place for the more radical avant-garde artists. Hans (Jean) Arp, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Richard Huelsenbeck were among the original contributors to the Cabaret Voltaire. As the war raged, their art and performances became increasingly experimental, dissident and anarchic. Together, they protested against the pointlessness and horrors of the war.

The Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich 1916 Photo: Frieze

Hugo Ball performing his poem, ‘Karawane‘ in the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 Photo: Wikimedia

The central premise behind the Dada art movement (Dada is a colloquial French term for a hobby horse) was a response to the modern age. Reacting against the rise of capitalist culture, the war, and the simultaneous modernist degradation of art, artists in the early 1910s began to explore new art or “anti-art”.

They wanted to contemplate the definition of art, and to do so they experimented with the laws of chance and with the found object.

Dada was an art form underpinned by humour and clever twists, but at its very foundation, the Dadaists were asking a very serious question about the role of art in the modern age.

This question became even more pertinent as the reach of Dada art spread. By 1915, its ideals had been led by artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Gloria Wood and Man Ray in New York, Paris, and beyond – and as the world was plunged into the atrocities of World War I.

The original group of Dadaists Photo: Frieze

Max Ernst, 'Women revelling violently and waving in menacing air' (1929). Photo: Daily Art Magazine

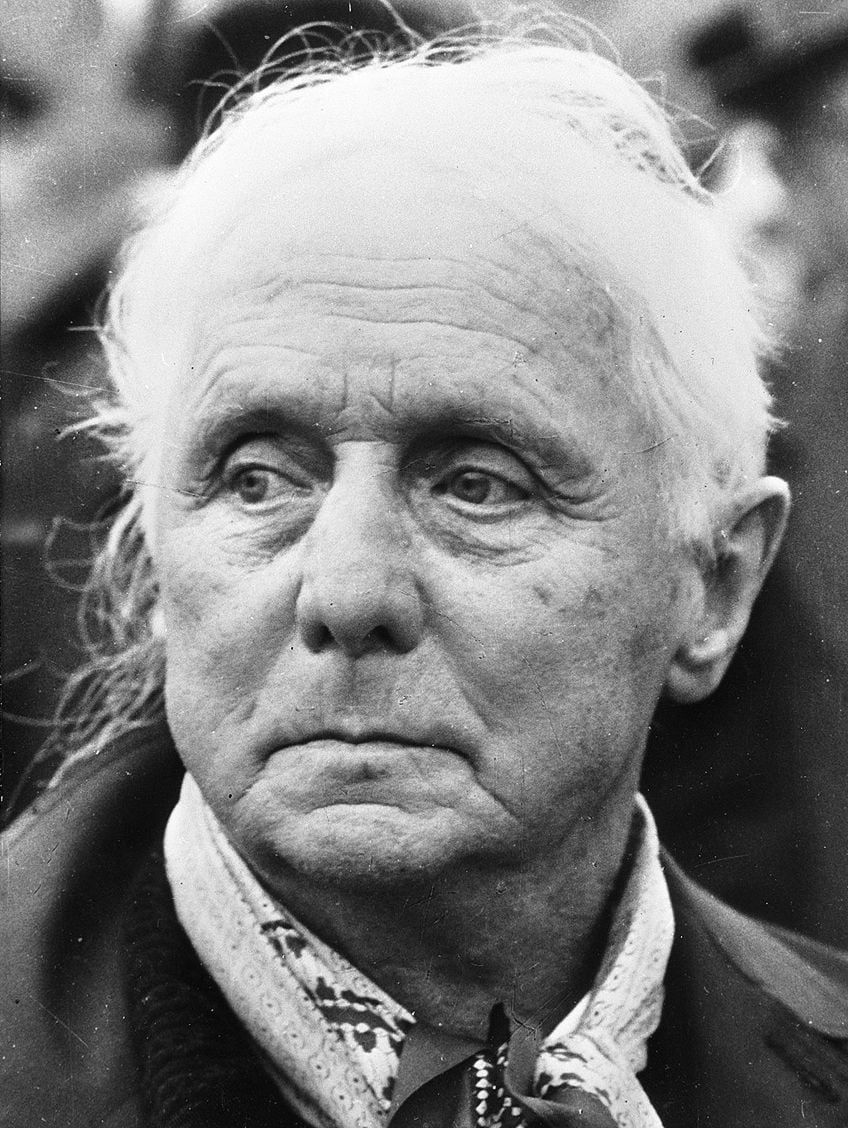

Tired by the Zurich artists’ cult of radicalisation and negation, Dadaist writers and poets broke away to explore more creative perspectives, arriving in Paris in the early 1920s. Initially the main preoccupation of the Paris Dada was literary and theatrical rather than artistic, but this changed with the arrival of the ‘subversive’ painter and collage artist Max Ernst in 1921. In essence, the Dada artists shifted gear, from the naturalism of the inner mind, mournful landscapes and spatial theatre of Surrealism to Dada’s parody and mockery of the distorted man-made or manufactured world.

Dadaism in Australia

Australia largely encountered Dada third-hand through the press during that initial period from its formation at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916 through to the official and perhaps premature pronouncements of its death in Berlin and Paris less than a decade later. The response was somewhat mute. It is only after Humphries’ Dada exhibition of 1952 and his subsequent outrageous, comedic performances in the name of Dada, that it appears to have entered the wider public consciousness as a form of anarchic expression.

Barry Humphries' 1952 exhibition Photo: University of Melbourne

At his first Pan-Australia Dada exhibition, Barry Humphries had packages printed up bearing the name Platitox, which allegedly contained a poison to put in creeks to kill the platypus, that much-loved, much-protected and playful native animal.

“So why have an exhibit which offers a pesticide to destroy these animals? Because everything was in its place in Australia,” said Humphries, who later told Who’s Who one of his hobbies was inventing his own Australia.

“On the package in small print it said it was also rather good for Aboriginals. Aboriginals didn’t exist; in a way, one was lead to believe that they lived a long way away and were dying out anyway. Which was terribly sad ... but there it was.

“This was all part of the tyranny of niceness and order. I didn’t want to overthrow order, I just instinctively wanted to give it a bit of a jolt so that people could see it.”[iii]

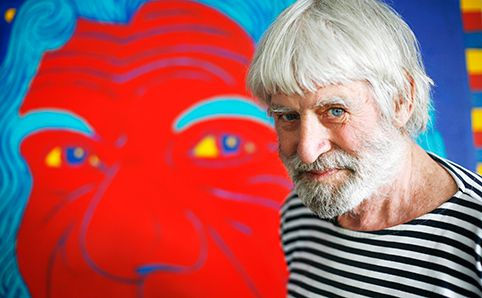

This late rebirth was followed during the 1960s by Dadaesque manifestations within Pop Art and the counterculture movement. Artists such as Martin Sharp and his colleagues at OZ magazine, including the writer Richard Neville and artist / filmmaker Garry Shead were active exponents and provocateurs, alongside the ever-outrageous Humphries.[iv]

Martin Sharp Photo: Berkeley Editions

Dadaism was ironically by virtue of its life source, brief. The very energy with which Dada proclaimed its nihilism involved a contraction that only could be sustained for a short time. Dada lived off acts from which it had to detach itself at the very moment it committed to them.

It swung without respite between formal concepts of liberty and living spontaneity, only mimicking the latter. The strain of constantly reinventing the present risked Dadaism becoming a stereotype. Its shocks were gimmicks. And nothing could be less dada than prolonging the life of something that had become sterile and repetitive. In a final humiliation, Dadaism was overwhelmed by the Surrealist position that gradually defined itself by reference to a discarded Dada.[iii]

In considering whether Dadaism can be said to have survived today one is reminded of the words of Mark Twain, “The report of my death was an exaggeration”.

Rene Magritte, 'The Red Model‘ (detai) Photo: Edward James Foundation

Dada in no small way is still alive. Unlike many other art movements, Dada’s influence has been far-reaching, embracing elements of contemporary art, music, poetry, theatre, dance and politics. At its core, Dada aimed at a climate on which art was unrestricted by established values; adopting techniques such as automatism, chance, photomontage and assemblage – and introducing the concept that an artwork could be a temporary installation. Dadaists expanded the boundaries and context on what was considered acceptable as art. Dada was anti-establishment and as described by one of its greatest proponents Marcel Duchamp, ‘anti-art’.

Importantly, Dada influenced the development of Surrealism, Action Painting, Pop Art, Installations and Conceptual Art. Dada was the essence of artistic anarchy that challenged the social, political and cultural values of its time.

The Art world owes much to Dada and Australia to Barry Humphries.

Hanna Hoch, ‘Incision With The Dada Kitchen Knife Through Germany's Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch' (1920) Photo: Smart History

Barry Humphries, 'Willie Weeties' (1968)(Print, 1989) Photo: Philip Bacon Galleries

George Grosz, ‘The Pillars of Society' (1926) Photo: Artnet

Max Ernst, 1968 Photo: The Guardian

Main photo: Barry Humphries AO CBE (2018)

[i] Suzanne Carbone, ‘Barry has a brilliant train of thought’, The Age, 16 November 2010 [ii] Graham Reid, 'Barry Humphries on the record: The early life of an agent provocateur’, Elsewhere, Auckland 2010

[iii] Michael Organ, ‘Dada goes dada’, Wollongong 11 May 2019

[iv] Robert Short, ‘Dada and Surrealism’, London 1980 p80

Comments