Brett Whiteley, Craig Ruddy and the renaissance of drawing and painting in Australian art

- Andrew McIlroy

- Jan 18, 2019

- 4 min read

Craig Ruddy’s powerful 2004 Archibald Prize winning portrait of actor David Gulpilil, with its intense, furrowed brow and piercing black eyes sparked a legal fight on the definition of the word ‘painting’.

Tony Johansen, a Sydney artist and regular Archibald entrant, argued the Art Gallery of New South Wales Trust should not have awarded the prize to Ruddy because his work was "not a painting but a drawing".

Johansen argued that because Ruddy predominantly used charcoal in his work, it was a drawing, not a painting, and therefore ineligible for the prize.

Ultimately, Justice John Hamilton of the NSW Supreme Court disagreed, dismissing Johansen's claim.

"I find it impossible on any objective basis to exclude the portrait from the category of a work which has been 'painted'," Justice Hamilton said.

('Art case thrown out', The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 June 2006)

In my mind this controversy – unremarked upon for the most part since - signaled a turning point in the modern Australian context in an appreciation of drawing as lying at the heart of painting and again finding its way to the forefront of university degrees, journal discourses, publications and museum exhibitions.

Craig Ruddy, 'Transformation' Photo: Richard Martin Art

Universities and art schools have returned for the most part to structured programmes that start with an intensive drawing course as the introduction to the underpinning systems and principles of visual language and painting in particular. The need for current exemplars such as Ruddy, is evident, more than anything to by their example ensure the vitality of students application and their practices.

Drawing then is understood to be fundamental to modern art practice, especially painting – as Ruddy, and Brett Whiteley and William Dobell before him will affirm - as both the most sophisticated and universally sophisticated means of thinking and communicating.

Whiteley stands as one of Australia’s great painters, but one cannot view or appreciate his work without equally measuring the value he placed on drawing.

Brett Whiteley Photo: AGNSW

Brett Whiteley, 'Lindfield gardens' (1984) Photo: AGNSW

Whiteley saw drawing as a tool of creative exploration. Of shaping artistic consciousness. Of developing imagination. Of enabling the visualisation and development of perceptions and ideas. Of observing and making sense of the worlds we inhabit. And the need to understand the world through visual means would seem now more acute than ever.

And while art practice today is assisted by the use of instant digital technology and computers to assist in composition, and with programs able to give dimension to form, such should be treated as a tool - independent of drawing - and not as a substitute or as a library for subjects and motives. Importantly, good art practice does not require the unification of thinking and drawing – the conscious drawing of every single line as supposed by technology and rejection of any compromises.

The practice of making art requires deeper analysis, of trying to reach the essence, and the evolution of thoughts through sketching.

Whiteley pondered various artistic techniques, desiring to master the skill of using them and to find their drawbacks and merits. Pencil sketching allowed him to note ideas quickly, in a less complicated and the less technologically advanced method of recording thoughts.

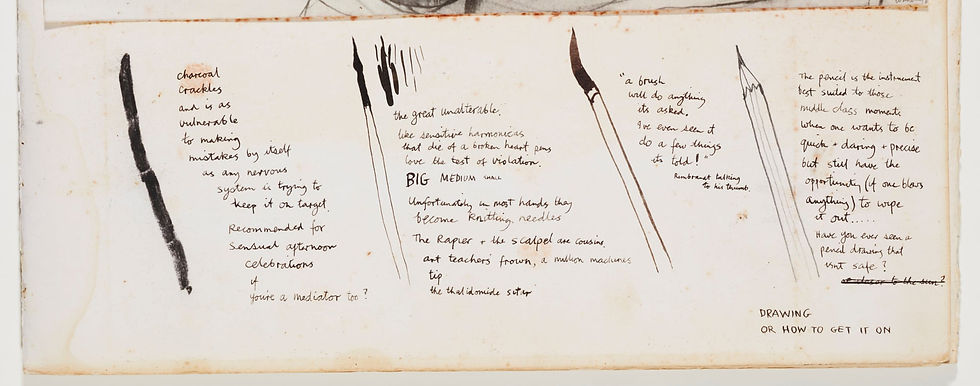

His diary notes currently on display at the AGNSW’s exhibition, ‘Brett Whiteley, drawing is everything’, insightfully read

The pencil is the instrument best suited to those middle class moments when one wants to be quick + daring + precise but still have the opportunity (if one blows anything) to wipe it out … Have you ever seen a pencil drawing that isn’t safe?

Brett Whiteley, Orange velvet sketchbook, detail from page 109 Photo: AGNSW

While great paintings through the centuries from Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarotti, Albrecht Dürer, Peter Paul Rubens, to Rembrandt van Rijn, Charles Le Brun, and Vincent van Gogh have founded on the skilled drawing hand of their masters, too many artists have failed to grasp drawing as fundamental and integral to good painting.

A sketch being unfinished and abstractive helps to express thoughts and make its evaluation no doubt easier. Its advantage is that it is both imprecise and precise.

The intangibility of a sketch allows one to interpret many meanings . Through a sketch, one may best and most simply communicate with recipients, remember seen images, discover. While sketching we observe nature and gain a better, more intimate understanding of reality.

Sketching introduces more expression and poetry into a drawing, and by emphasising individual features, elements and form, they are inevitably close to reality. As an inseparable part then of the painting process, their value is immeasurable.

With artists. galleries, academics and institutions focusing once more on the primacy of drawing in painting, the distinctions that had found their way into the consciousness of a staid art world have thankfully fallen away, breathing new life into an old medium. It seems to have taken artists of the intensity of Whiteley and Ruddy to bring the transformative power of drawing into plain view.

Brett Whiteley, Self-portrait in the studio (1976) Photo: AGNSW

Brett Whiteley, King Pigeon (1985-1988) Photo: AGNSW

‘Brett Whiteley: Drawing is everything’ at The Art Gallery of New South Wales runs till 31 March 2019

Main Photo: Artist Craig Ruddy

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist and arts writer, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Comments