Alfred Felton and Frederick Grimwade: The abiding friendship that gave birth to the NGV collection

- Andrew McIlroy

- Nov 20, 2018

- 6 min read

The thoroughfare of Flinders Lane has long been familiar to the people of Melbourne with its grand heritage buildings, such as the iconic Chapter House (1891) designed by the famous British architect William Butterfield, a testament to the extraordinary wealth of Melbourne in the years following the gold rushes of the mid 19th century. But Melburnians owe much more than is first apparent to this narrow lane-way's ornate facades, textile stores and warehouses that once flourished.

Among the chaotic growth of Flinders Lane through the 1880’s and ‘90’s, this bluestone, industry-lined street gave rise to two of the city’s great philanthropists and curiosities, industrialists Alfred Felton and Frederick Grimwade, and the birth through this abiding friendship of one of the world’s great public art collections.

Flinders Lane’s story, with its eclectic modern-day mix of offices, cafes and prominent art galleries in so many ways then lies at the heart of Melbourne’s artistic pre-eminence today.

Fritz Kricheldorff (attributed to), 'Flinders Lane, Melbourne' (1890s-1920s) Photo: NGV

Robert Hoddle, artist and surveyor general of the Port Phillip District from 1837-53, designed the new settlement of Melbourne with wide streets. But the New South Wales Governor, Richard Bourke, insisted on inserting smaller parallel laneways. Bourke wanted there to be rear access to the city's buildings 'to give owners the means of getting cows in and out of their backyards'. (Russell Grimwade, Flinders Lane, Recollections of Alfred Felton, Miegunyah Press, 1947)

Hoddle ceded the Governor his "Little Streets", gazetting Little Flinders Street in September 1843 and Little Lonsdale, Little Bourke and Little Collins streets five months later in 1844.

However, decrees from the Colonial Office in NSW regarding Melbourne sometimes had limited effect on the people down in Melbourne.

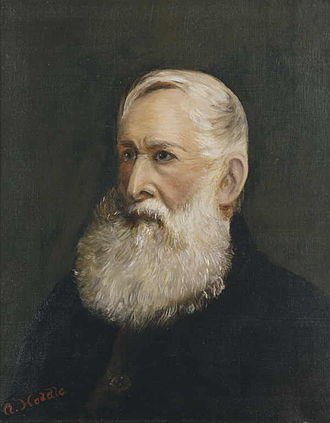

Robert Hoddle, oil painting by his daughter Agnes McDonald circa 1888 Photo: State Library of Victoria

In the 1840s, so-called Little Flinders Street was known for being home to some particularly rowdy pubs. But as the 20th century neared, Little Flinders Street became the centre of the city's clothing industry or "rag trade". The street was affectionately known as "the Lane", with the rag traders who dwelt there dubbing themselves "Lane-people” and who began the push for the council to recognise Flinders Lane as the one-and-only name for the street.

In the end according to local historians there was a sense that Flinders Lane had some other kind of pre-eminence in the consciousness of the settlers.

View of Flinders Lane c1890

It was here Alfred Felton born in East Anglia in 1831 and arriving in Melbourne in 1853 and who began his fortune selling 'Felton's Quinine Champagne' to miners during the gold rushes, partnered with Frederick Grimwade to establish a successful pharmaceutical company, Felton Grimwade & Co., building 'the handsomest drug house in Australia', an imposing bluestone warehouse. (Grimwade)

The erudite Grimwade, a pharmacist and later parliamentarian, shared Felton’s duty to philanthropy, and love of art, architecture and conservation. It was the fruit of this close pair’s friendship and their determination to preserve the nation’s artistic heritage (as they saw it) that was to be felt at every level of Melbourne society, through the ensuing century to the present day.

Before long their burgeoning business moved into glass manufacture, making Felton and Grimwade rich men.

Frederick Sheppard Grimwade (10 November 1840 - August 1910) was a businessman and Victorian Member of Parliament

The Felton Bequest

“Wealth!! Get it spent", scribbled Felton in his diary in September 1903. Four months later, on January 8, 1904, breathing his last in a simply furnished bedroom in St Kilda's Esplanade Hotel, leaving a will that contained the most fabulous arts bequest Australia has ever seen. ('The bequest of the century', The Age, 12 January 2004)

A grand sum of £383,163 - $40 million in today's money - was bequeathed to art and charity, with half of the interest earned to be used in perpetuity to buy works for the National Gallery of Victoria. In one grand gesture, Felton had transformed the NGV into one of the most lavishly endowed public galleries in the British Empire with greater funds at its disposal than London's National Gallery and the Tate combined.

In the century since his death, about 17,000 works of art have been bought with the bequest, now valued at more than $2 billion. That selection includes works by Rembrandt, Tiepolo, Monet, Cezanne, van Gogh, and Turner to name but a few.

Giambattista Tiepolo, 'The Banquet of Cleopatra', (1743-1744) Photo: NGV

Through it all though, while Felton was no recluse, he never put himself up for public office, never sat on public committees, and he never married, so that when he died at the Esplanade Hotel he left no heirs.

Felton had been a collector of art since 1887, says his biographer John Poynter, displaying what has been described as "an understandably nostalgic liking for English scenery".

He is known to have become a patron of one living artist, Rupert Bunny. Poynter relates that Felton knew his father, Judge Brice Bunny, and that according to Bunny family tradition Felton persuaded the judge to allow his son, bound for duty in an architect's office, to enrol in the National Gallery School in 1881. (The Age, 12 January 2004)

Felton continued to support the artist's work, commissioning 'Saint Cecilia' in 1889. Still, when Felton died, Melbourne's art world expected that at best the bachelor might donate to the gallery the works adorning the walls of his rooms at the Esplanade Hotel or his many properties.

Rupert Bunny, 'Saint Cecila' (c1890) Photo: Artnet

Felton had been deeply involved in some Melbourne charities but never been directly involved with the gallery - his only connection had been donating St Cecilia.

"In other words," says Poynter, "art was one of his very strong interests but there was no indication before his death that he was likely to set up this art bequest."

The timing of the bequest was as fortuitous as its scale, allowing the NGV during the first half of the century to build a comprehensive collection including great European masters, Chinese art, and sculpture, before art prices began to spiral in the late 1950's.

"It was extraordinary good fortune for the gallery to have the regular income at that time," says Poynter. "You couldn't build a collection like this any more. With major works of art going into public collections and prices rising it would be impossible."

Alfred Felton's rooms at the Esplanade Hotel, St Kilda Photos: NGV

The breadth of the collection has also been a benefit, given changing tastes in the art world. "The Tiepolo for instance (Cleopatra's Banquet) is now thought of as one of the really great pictures of the world. They bought it in the early 1930's at the same time as a Rembrandt, which turned out not to be genuine. But at the time they were far more interested in the Rembrandt.

"The lesson is that galleries really should keep things," says Poynter. "In the middle of last century they got rid of some Victorian works that nowadays people would like to have. It was useful advice that Felton's lawyer P.D. Phillips gave that the gallery had to keep any purchases made with the Felton Bequest."

Professor John Poynter (2009) Photo: University of Melbourne

The bequest carries on now, into its second century, purchasing works of art that Felton could never have imagined, at prices Felton could never have imagined, but all with money that can be traced back to Victoria's golden era.

"Felton was one of the great merchants of the gold rush era when Melbourne was the dynamo of the Australasian economy," says Poynter. "This was not a public figure, not a politician, but he was one of the important (figures) in Victoria. I think it's a symptom of just how rich and varied that era was that a person as interesting and important as him isn't better known."

Among the community of Lane-people, Felton and his polymath friend and fellow benefactor, Grimwade, would no doubt have cut formidable figures. It was no doubt their deep conversations on Flinders Lane's sidewalk on art, business and Melbourne culture gave rise to what can be seen as a great joint enterprise, the Felton Bequest, and indeed to one of the world's great public art collections.

Chapter House entry today, Flinders Lane, Melbourne Photo: Chapter House Lane

The Esplanade Hotel (c1890) Photo: State Library of Victoria

Main Photo: Alfred Felton and Frederick Grimwade (1890) Photo: NGV

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist and arts writer, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Comments