From Paris to St Kilda: Alfred Felton and his passion for 19th century Romantic Art

- Andrew McIlroy

- Sep 28, 2018

- 5 min read

As art institutions from London’s Tate to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art revisit and examine the far-reaching influence of European art with significant new exhibitions featuring the great Romantic artists such as Eugène Delacroix , Andrew McIlroy reflects on the influence of 19th Century European art and artists on the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, and on the city it calls home.

On the eve of the Summer re-launch of one of Melbourne’s most dearly-loved institutions, St Kilda’s Esplanade Hotel, the sentimental and stirring human stories emerging of iconic bands, celebrities, bohemians, knockabouts and drunkards that have made this decaying building their home affirm why this old pub is so important to this city’s identity and so many Melburnians. Everyone it seems has a personal connection to and story about ‘The Espy’.

Yet the place of 'The Espy' in the heart and history of Melbourne goes deeper. It has not always been a haven for the homeless, hedonists and misfits. This Italianate 19th century hotel was once a grand home and a favoured weekend destination for some of the city’s most influential and wealthy citizens.

Facing the wrecking ball numerous times over the last decade, the local arts community and others rallied. In the end their efforts were rewarded and the pub was ultimately saved from demolition.

The Esplanade Hotel (c1890) Photo: State Library of Victoria

The Esplanade Hotel, St Kilda in recent times

This past year has seen the hotel undergo extensive renovations by its new owners, exhuming the many boarding rooms that once made up its upper levels, including the former lodgings of Alfred Felton, an avid art collector and long recognised as the benefactor who transformed the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

Since Felton’s death in 1904, the Felton Bequest he established has enabled the NGV to amass a collection of artworks today valued at more than $1.5 billion, that includes works by Rembrandt, William Blake, Tiepolo, Monet, Cezanne, van Gogh, and Turner to name but a handful, and made the gallery the envy of institutions throughout the world.

Felton's rooms at the Esplanade Hotel, circa 1900

But growing up in Melbourne’s football-mad, eastern suburbs during the ‘70’s, I may as well have been living on a remote atoll, far from the treasure trove of the NGV for all I knew of art and our great shared fortune gifted by Felton.

I am not sure which came first, a fondness for the Espy (and beer) or my love of art. But at this stage of my life I have come to realise that the two for many Melburnians inextricably linked and form no small part of our shared subconscious.

Thanks to Felton the NGV’s collection today is as rich and eclectic as that of any great institution throughout the world, successfully traversing eras and genres. But for me, one space within its walls defies remains extant, defying trends and modern-day fancies, and holding those who pass through enthralled.

And while the 19th century, salon-styled gallery - mirroring Felton’s own boarding house aesthetic - holds more than a 140 works of European and painting and sculpture from a long-passed era, the gallery keeps the display fresh and relevant here, replenishing the walls with a selection of contextualised 19th and early 20th century Australian works, including those by Arthur Streeton and David Davies.

Re-hanging the NGV's 19th century Salon (2018)

Johan Bennetter’s majestic ‘Fight between the ship of the line, Jupiter and the French frigate, Preneuse, in the neighbourhood of Madagascar 11th October, 1799' (1866) dominates the eastern wall on entry. Equally powerful, Jules Bastien-Lepage’s 'October' ('Saison d’octobre') sits opposite. Edwin Landseer’s Shakespeare-inspired painting, 'Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Titania and Bottom', is too prominently displayed.

August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck’s popular and emotive painting 'Anguish', 1878 – depicting a ewe protecting a dying lamb from a murder of crows – continues to hang proudly, but those much smaller works and equally exquisitely painted clustered around have until now remained hidden. Amongst these, one small work takes my eye, Eugène Delacroix’s, 'The Confession of the Giaour' ('Confession du Giaour') (c1825) – purchased from the collection of François Thiebault-Sisson in Paris by the Felton Bequest in 1910.

August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck, 'Anguish' 1878

Johan Bennetter, ‘Fight between the ship of the line, Jupiter and the French frigate, Preneuse, in the neighbourhood of Madagascar 11th October, 1799' (1866)

Edwin Landseer, 'Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Titania and Bottom'

Arthur Streeton, 'Corfe Castle' (1909)

Eugène Delacroix, a favourite of Felton, was the embodiment of 19th century French Romanticism. He was a leader of the Romantic Movement, and is regarded by many as a forefather of modernism, with Picasso, Cézanne and van Gogh hailing him as a genius.

“Delacroix’s palette is still the most beautiful in France,” Cézanne once marked. “We all paint in his language.”

Or as Picasso told the painter Françoise Gilot: “That bastard. He’s really good.”

French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) (Self portrait)

Delacroix’s influence on the NGV’S collection and its significance to the collection as a whole is greater than the mere size of this small canvas.

Delacroix resisted painting current events that would date his work, Fixing it to an historical event or time, preferring to draw from history and classical genres. In contrast, his mentor, Théodore Géricault, took up the banner for Romanticism at the 1819 Paris Salon with his large-scale “Raft of the Medusa,” which depicted the gruesome aftermath of an 1816 shipwreck. (Delacroix posed for one of the dead bodies.)

Eugène Delacroix, 'The Confession of the Giaour' ('Confession du Giaour') (c1825)

Except for 'July 28, 1830: Liberty Leading the People' — Delacroix’s homage to the July Revolution — you would never know that he lived through three regime changes, from Napoleon’s abdication, to the Bourbon Restoration and the July Revolution that brought it down, to the 1848 overthrow of Louis-Philippe.

Delacroix preferred subjects from the Bible, Shakespeare, Walter Scott and especially the poems and tales of Byron, as well as scenes from exotic cultures made accessible by French colonialism.

“The first merit of painting is to be a feast for the eye,” Delacroix wrote in June 1863.

The Salon, National Gallery of Victoria

It’s intriguing to think of Delacroix’s love of narrative and history as driven by a need to shut out the tumult of his time for the sake of his art. But thankfully Delacroix’s thought and use of tone encapsulated in 'The Confession of the Giaour' give his works their lasting and universal meaning, transcending time and giving us much to reflect upon and celebrate. The NGV’s Salon is full of such treats.

The Felton Bequest is an enduring gift, and connects us all in ways we perhaps at first do not realise. We should perhaps too remember that when we next raise a glass at The Espy.

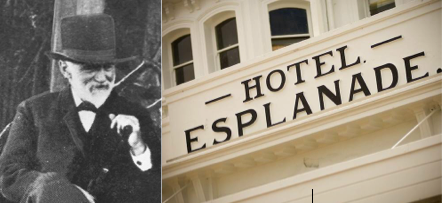

Main photo: Alfred Felton and the iconic Esplanade Hotel

Delacroix runs until 6 January, 2019 at New York’s Metropolitan Musrum of Art.

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist and arts writer, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Jules Bastien-Lepage, 'October' ('Saison d’octobre')

Comments