Fred Cress: An outsider's passionate portrayal of lust, greed, hate and envy

- Andrew McIlroy

- Jul 21, 2018

- 5 min read

I once met Fred Cress. He was sipping tea outside a small café near his home in the hip Sydney inner-suburb of Annandale, watching intently and engaging with those around him. On this day, Cress lauded for his riotous and vivid figurative painting was erudite and unassuming as he spoke of his work towards what would unbeknown to all be his last exhibition at Australian Galleries in Paddington.

Cress’ long time friend Annette Larkin says that the artist relished spending time with friends, new and old, but he also saw these social occasions as an opportunity to gather subject matter for many of his paintings. He was fascinated by people’s behaviour and the gamut of emotions — lust, greed, hate and envy — and also people’s relationships and their secrets. (‘Fred Cress: After an opening’, The Australian, 16 December 2017)

Cress died on 14 October 2009, at the age of 71 from prostate cancer.

Fred Cress with his 1988 Archibald winning portrait of John Beard Photo: The Age

Speaking on his death, then director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Edmund Capon said, ''Fred was a very singular and independent voice in Australian art. He went from abstraction to figurative work, but always with personal characteristics - one of which was a strong graphic sense, and another, a strong colour sense.'' (Steve Meacham, 'Surrounded by family, Cress gets his final wish', The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 October, 2009)

This year Cress would have turned 80. To acknowledge the anniversary, Australian Galleries in Sydney is holding a retrospective of his work, featuring key works from the artist’s archives – previously reserved for his private collection – tracing his oeuvre from 1965 to 2009. The exhibition traces the stylistic shifts propelling Cress’ artistic evolution, including to the astonishment of many turning his back on abstraction in the mid-1980s with the introduction of recognisable objects, figurative forms. Cress described his life to art critic and author Sasha Grishin as a journey of struggle and self-doubt.

Fred Cress, Night Runners, 1993 Photo: Australian Galleries

Grishin recounts a conversation with Cress in 2001 where the artist expressed his heartfelt concerns with his place among and the work of his contemporaries.

When I came back from … New York (in 1974) I was a worried man and not the confident artist which I was made out to be. The conclusion I had come to was that the problem lay with drawing – the fact that these artists did not draw worried me. For me, drawing was important because that was where touch lay, where intimacy lay, where your total individuality lay – that was the way you could tell who was an artist and who was not.”

In 1982, after a tumultuous period in his personal life and a brief respite in India, Cress returned to Australia with a renewed perspective.

I came back with narrative in my mind and felt that Western painting had lost a most important thing when it could not tell stories, because we were told not to tell stories as this was not in the true interests of painting and not in our best interests as artists. I also came back wanting to make painting much more enjoyable again, filled with colour and strong tone and if you are using narrative you give yourself a lot to draw because you drag into your orbit many more shapes and situations. It doesn’t work just to tell the same story again and again. … Because I was still an abstract painter, I first tried to put it all into abstract painting and it was not until 1988 that the pressure for figuration became too great, so in 1988, at the age of fifty, artistically I became totally myself.”

Fred Cress, Otherselves, 1993 Photo: Australian Galleries

Grishin observed,

Cress likes to draw a parallel with Goya, and the myth of the divided genius, who in his early life was the fashionable painter who nostalgically clung to the frivolity of the Baroque, only to be reborn, when aged about fifty, as the innovator and visionary. This dark twin engaged with the romantic imagination, denounced the horrors of war, the hypocrisy of the church and the fear and superstitions of the masses, one who towards the end of his life painted mystical black paintings and who died in exile in France.

(Sasha Grishin, ‘Fred Cress: Figured it out’, Art Collector, Issue 38, October – December 2006)

In 1988, Cress was awarded both the Archibald Prize for his portrait of fellow artist John Beard and the People’s choice award. In 1995, Cress was the subject of a survey exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and "enjoyed high profile success with a plethora of highly successful solo exhibitions of his figurative work". "Fred Cress liked to observe society from behind the scenes", says Grishin, "as a passionate outsider commenting on the follies of humanity and the passing parade. This voyeuristic aspect, laced with sinister enjoyment, sets up a discourse between the artist and his subject and we the audience are invited to adopt partisan positions. The situations and the realities which he describes are known to all of us and the artist adopts an ethical stance where on one hand he appears to condemn the foibles, greed and stupidity of the situations which he describes, on the other, the irony and sensuous eroticism which he introduces into his scenes suggests that he secretly enjoys the experience."

Early abstraction: Fred Cress, Red Thoughts (formerly knave of hearts) 1965 Photo: Australian Galleries

As outsiders like Cress we are pulled bemusedly to his cleverly drawn, misbehaving figures. Our attention too is seized upon how the paintings are made with their graphic gestural strokes and unifying colours, and the psyche of the artist behind them.

I agree with Paul McGillick's in his Artist Profile review of Fred Cress: Full Circle (9 July 2018) that Cress' "figurative elements work in harmony with the formal character to animate the painting and provide the frame for generating aesthetic meaning". In this way, Cress' paintings "demand the active participation of the viewer".

In this Australian Galleries exhibition we are privy through an exploration of these works to the fascinating journey of this widely travelled polymath, taking him back as McGillick observes full circle to where it all began. Hopefully, there will be a good party or two to follow.

Fred Cress | Full Circle – Paintings and works on paper 1965-2009 in collaboration with Annette Larkin Fine Art runs to 29 July at Australian Galleries, Sydney

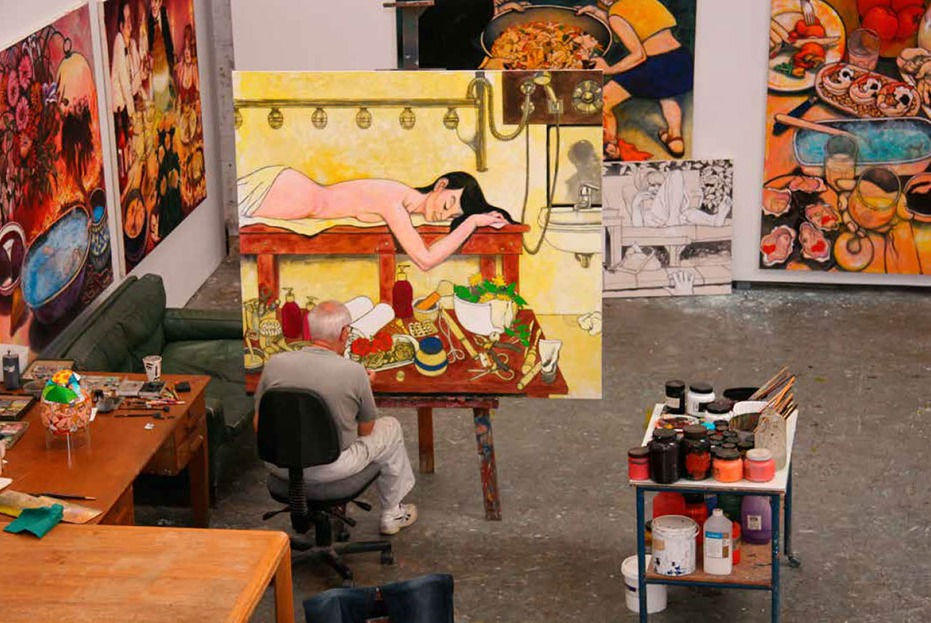

Fred Cress in his Sydney studio 2008 Photo: Australian Galleries

Main Photo: Fred Cress, A pool party, 1996 Photo: Australian Galleries

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist and arts writer, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Comments