The shaming of sexual desire, eroticism and voyeurism: Remaking the female nude in contemporary art

- Andrew McIlroy

- May 11, 2018

- 6 min read

The female body in an artistic form has always been capable of arousing sexual desire. From playfully seductive, neoclassical portrayals to surrealist muses depicting impulsive lust, female bodies throughout art history have been objects of desire and self-gratifying pleasure.

Yet modern-day artists appear more interested in presenting the female body as a non-sexualised object in their efforts to subvert traditional meanings or as an extension of their storytelling - ascribing to female bodies an ability to rise above an individual’s need for self-gratification.

There is no doubt this genre has earned its valued place in the tradition of art. Indeed, it well reflects the fast changing social order under which such art is made. But at what cost? Is the beauty and once emancipating eroticism of the female form being subjugated by the moral censures of today, reflected in the social movements such as #MeToo that seek to de-objectify women? Is modern art-making exemplified by the art of photography that captures raw emotion and imagery in a single moment raising the art of symbolism above all else?

Miru Kimm, Old Croton Aqueduct, Bronx NY USA 2006 (detail), C Print

This is not to suggest that contemporary artists across all creative disciplines have been more active in challenging conventions than the artists of the modern era (from the 1860’s to the 1970’s). Using the female form as an embodiment of protest and to rail against convention is not new. It is just that nowadays artists appear fearful of or in the least reluctant to challenge the moral orthodoxy that says one cannot portray woman as the object of sexual desire that today seems somehow offensive.

The result sees the female body as an emblematic or symbolic device rather than as a study of sexuality and sensuality. There remains then a stark contrast between the sober representation of the female body in contemporary art and the raucous celebration of female sexuality of the not-too-distant past.

Celebrating sex in art

Édouard Manet in the period that gave birth to Impressionism challenged classicism’s idealised depiction of the nude when he first exhibited ‘Olympia’ in 1863. Despite referencing a classical representation of the female nude in Titan’s ‘Venus of Urbino’ (1538), Manet challenges the viewer by bringing to the fore the subject’s sexuality, instead of its idealised beauty. While the young woman in the painting shares the same pose of Titan’s ‘Venus’, Manet draws attention to her non deity-like appearance, since her necklace, black cat and shoes explicitly suggest that she is a prostitute.

Manet here is not yet freeing the woman from her status as a passive object to be admired. Rather, he is making a statement on the voyeuristic nature of art.

Édouard Manet, Olympia (1863)

Following Manet, various painters such as Paul Gauguin, Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud disrupted the conventional display of female bodies, offering the viewer new ways to look at them while retaining their erotic essence.

Gauguin, revered as the pioneer of the inventive Fauvist movement that linked the unconventional, highly subjective use of colour to the emotion that the subject inspires rather than to the subject itself, focused on the sensual depiction of Tahitian landscapes and native women – a traditional subject again displayed in an unconventional way.

Gauguin’s Manao Tupapau references Manet’s Olympia and, when first exhibited,was called the “Olympia of Tahiti”

At the beginning of the 20th century, the portrayal of the essential sensuality of the nude was not yet forsaken. While many painters were depicting women as threatening and the like, Egon Schiele drew towards their beauty and sexuality. Schiele completely rejected traditional depictions of women in stereotyped positions, and instead experimented with female portraits in various postures and with different body shapes.

Schiele’s Woman Touching her Breast (1910) is explicitly erotic

In his depictions of female nudes, Schiele brings to the fore this unhealthy and suppressed sexuality, portraying bodies that are consumed by uneasiness and by marks of sinful indiscretions.

Francis Bacon’s nudes are equally confronting. His work Reclining Woman (1961), depicts a naked woman in a confident and almost aggressive position. Here the female nude is clearly not an object for the male gaze, as it is distorted and unclear. It challenges the viewer, displaying a confident and forceful subjective sexuality, which makes her, rather than an object of sexual desire, an embodiment of it.

Francis Bacon, Reclining Woman (1961)

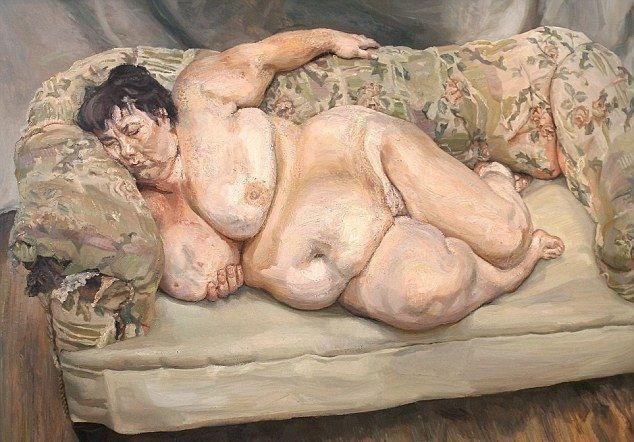

In Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, Lucian Freud portrays unconventional beauty and its erotic quality. Freud not only goes against the tradition of the artistic representation of the female nude, but also defies the prevailing obsession with stereotypical beauty.

Lucian Freud, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping

From sensuality to symbolism

Until recently, the female nude in art retained its heightened sexual and erotic nature as essential to its purpose to challenge societal and artistic conventions. And while there has been and still are artists who use the female body to depict sexuality, the pendulum has swung to perhaps favour those other artists able to portray the complete opposite. These artists’ tend to reflect on universal themes, which the female body symbolises, so that observers see the female body as a part of themselves rather than a sexual object.

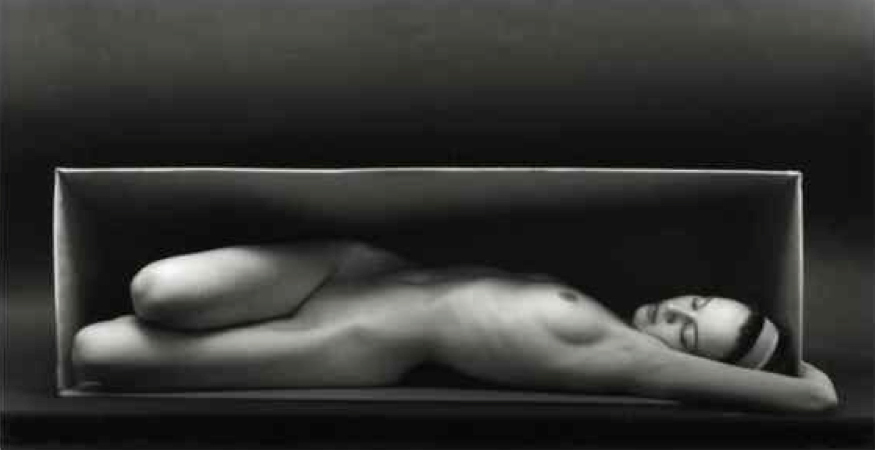

A shift was evident in the aftermath of World War II. Ruth Bernhard’s photography is most widely known for her studies of female bodies. Bernhard aimed to reflect the female body as a natural, rather than as a sexual entity through minimalist aesthetic and black and white photography.

Ruth Bernhard, In a Box (Horizontal) (1962)

In a Box (Horizontal) (1962) reflects Bernhard’s representation of the female body’s vulnerability. The use of enclosed space creates an interpretation that the female body can be threatened through any form of violence.

At the forefront of this trend to desexualise the naked human form in contemporary art is the celebrated New York-based artist Spencer Tunick, famous for staging mass nude photographs. The artist having staged 125 mass nude installations in 25 countries describes his work as “transcending difference, and foregrounds the humanity in our industrialised lives”.

Spencer Tunick, Mexico 2007

In 2007, Tunick staged his biggest ever installation with 18,000 people posing naked in Mexico City's central plaza. However, the artist said it was "not so much about the numbers" but about engaging people and creating "a new dialogue ... about the body in a public space". (Hannah Francis, Spencer Tunick returns to Melbourne for mass nude photographs in 2018, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 2018)

Tunick defines the naked human body as an extension of humanities’ connection with our natural environment, “the bodies extend into and upon the landscape like a substance. These grouped masses which do not underscore sexuality become abstractions that challenge or reconfigure one’s views of nudity”. Tunick’s aesthetic direction is to personify female bodies in reaction to their surroundings – quite a contrast to Manet’s “Olympia”.

American artist, photographer and illustrator Miru Kim too presents the nude as symbolic, rather than as an object of desire. In her photographic series 'Naked City Spleen', Kim’s aim is to merge her physicality with urban spaces. As a result, Kim says “I momentarily inhabit these deserted sites, they are transformed from strange to familiar, from harsh to calm, from dangerous to ludic”. Kim uses her body as a representation of humanity, how we are physically and consciously connected to our surroundings, a relationship which can be flawed. (Kim M, ‘Populating My Solitude', 2008, www.mirukim.com)

Miru Kimm, Michigan Central Station, 2011, C Print

It is self-evident that art is the product of a society, reflecting its nature and history. Art also has a deeper meaning that reveals something truthful to the society; a revelation that can carry a society into a new era, laying bare the conventions and fallacies of the old.

Understanding the world and times in which art is made does enable us to form a judgement. But turning our backs on a form of art, most notably the erotic and sexual portrayal of the female naked form, by assigning it to a bygone era whose representations are abhorrent perhaps by today’s moral standards leaves us with potentially overly-intellectualised work, dripping with high-minded symbolism, and ultimately lacking authenticity. And art without authenticity, is not art.

Perhaps in this perverse way, reviving the erotic and sexual depiction of the nude is a desirable path by which today’s artists can challenge the conventions of the modern, politically correct world in which we find ourselves.

Spencer Tunick installation in Munich

Miru Kimm, Demolition Zone, Moraenae, Seoul, Korea 2009

Main photo: Spencer Tunick, Vienna Austria 2 (2008)

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Comments