Aida Tomescu, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock: A single act of vandalism helps unlock the mystery

- Andrew McIlroy

- May 17, 2018

- 5 min read

Wherever they are displayed, Australian artist Aida Tomescu’s monumental abstract paintings draw a crowd. There is something richly compelling and authentic about them. Since emigrating from Romania in 1980, Tomescu’s “full-throated painterly abstractions, where colour and gesture flow through the work” are deservedly held in high regard among the in-crowd.[1] However, the appeal of Tomescu’s work and that of other abstract expressionists to outsiders remains a bit of a mystery.

The paintings might appear to be the result of addition and spontaneity”, says Tomescu, “but for a painting to achieve the unity I want, there is a lot of erasure – every work is ultimately born more of disruption and erasure”. [2] The heavily painted and distressed surfaces of Tomescu’s works clearly give witness to her effort, and give the paintings their emotional punch.

Aida Tomescu (b1955) Photo: Ocula Conversation

Understanding the artist’s emotional state of mind and the techniques employed in giving them expression lie at the heart of appreciating abstract art. And that may not have been so widely understood but for an infamous event in London in 2012 that forged a new way of looking at this once maligned field of artistic endeavor.

It was approaching late afternoon one day in October of that year at London’s Tate Museum (now Tate Britain) when, say astonished witnesses, a man in his late 20’s calmly walked up to Mark Rothko’s ‘Black On Maroon’ (1958) and scrawled a graffiti message in bold, black marker pen. The iconic painting - one of nine interrelated Seagram murals gifted to the Tate in 1969 by the artist because he was sickened by the idea of “these great and worrying visionary masterpieces” ending up in the place originally planned for them, a high-class New York restaurant - seemed ruined.

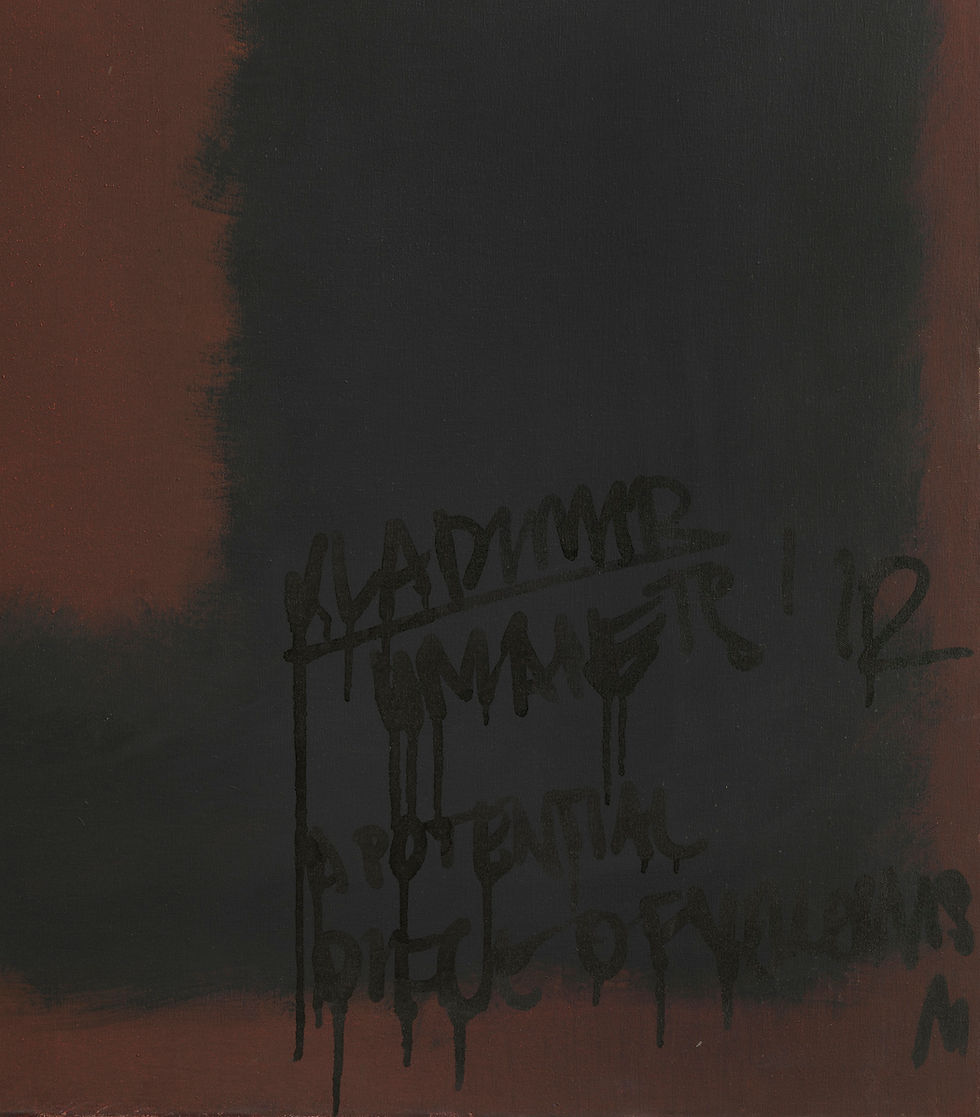

Graffitti stains Mark Rothko’s Black On Maroon (1958)

The graffiti read, “Vladimir Umanets, A Potential Piece of Yellowism” - an apparent reference to an obscure and somewhat tortuous view at the time that while conceptual art can look like works of art, they are not works of art.

The visible damage was significant and as the painting was delicate, degraded and unprotected by glazing or a coherent varnish coat, the attack was to challenge conservators. The painting’s repair would firstly necessitate an in-depth study of Rothko’s unorthodox working practice, his materials and techniques. What followed was revelatory.

Little is known of Rothko’s technique and he preferred it that way. He delighted in the idea of secrecy and silence, dismissing attempts to ask him about his methods as “too professional an inquiry” and often adding, ‘some artists want to tell all like at a confessional. I as a craftsman prefer to tell little’.

Mark Rothko (b1903 - d1970)

Rothko was concerned with the permanence of his paintings and his attempts to achieve this were peculiar to themselves, largely experimental, innovative in choice of materials and difficult to dissemble. Roy Edwards, his assistant when working on the Harvard Murals, remarked in 1971 “he was always reading these books on how to make paintings more permanent”.

This led Rothko to make choices that were on occasion at odds with his concerns for longevity, such as moving between opaque and translucent layers, risking the paint separating or unfixing - and pared back via a scumbling process to counter this.

The scars of Rothko’s experimentation perversely gave effect to the permanence he so fastidiously sought. Rothko’s experimental, fast-paced method joined the artist to the genre he so earnestly resisted.

This experimentation lent weight to the comparison of Rothko to the often-maligned ‘Action Painters’, whose approach to painting emphasised the highly physical act of painting as an essential part of the finished work and where paint is spontaneously dribbled, splashed or smeared onto the canvas, rather than being carefully applied – a style of working epitomised by Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning.

Willem de Kooning, Police Gazette (1955)

Franz Kilne, Orange Outline (1955)

The resulting work often emphasises the physical act of painting itself as an essential aspect of the finished work or concern of its artist.

Published in New York’s ArtNews in December 1957, Rothko wrote a letter to the editor, complaining that its editor Elaine de Kooning had mistakenly classified him as an Action Painter.

Sir,

Re Two Americans in Action [A.N. ANNUAL ’58]: I reject that aspect of the article which classifies my work as “Action Painting.” An artist herself, the author must know that to classify is to embalm. Real identity is incompatible with schools and categories, except by mutilation.

To allude to my work as Action Painting borders on the fantastic. No matter what modifications and adjustments are made to the meaning of the word action, Action Painting is antithetical to the very look and spirit of my work. The work must be the final arbiter.

Mark Rothko New York, N.Y.

Qualifying her use of the term, de Kooning replied “except for the appearance of the large image - and the large image can appear in many forms - there is no exclusive “look” to Action Painting … The “action” is not necessarily the action of pushing paint around as many Europeans and Japanese apparently take it to be”.

Elaine de Kooning Photo: The Art Story

Clement Greenberg, an influential American critic in Action Painting, added a further dimension that may have calmed Rothko so concerned to distinguish the ultimate “look and spirit of his work” from the process of its creation – perhaps because in no small part his hit-and-miss process was not of a fine artistic tradition.

Greenberg was intrigued by the creative struggle, which he claimed was evidenced by the surface of the painting. To Greenberg, it was the physicality of the paintings' clotted and oil-caked surfaces that was the key to understanding them. In this way the emphasis of the paintings shifted from the object to the struggle itself, with the finished painting being only the physical manifestation of the actual work of art, which was in the act or process of the painting's creation.

Art critic, Clement Greenberg (b1909 - d1994)

When Rothko was joined by his compatriot artists Rothko, Jackson Pollock (who was killed in a car crash three years earlier), Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning, Clyfford Still and others in the London exhibition The New American Painting in 1959, Europe’s modernist painters struggling to free themselves of the existentialism grip on their oeuvre were enthralled.

The new American painting, by contrast, involved vast canvases by Pollock, with attention-grabbing energy and directness, and an emotional impact that, in Rothko’s case, reduced some viewers in was said to tears - “they are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them,” Rothko would explain.

Jackson Pollock, Conversion (1952)

Until the single act of vandalism in 2012, against Rothko’s ‘Black on Maroon’, abstract expressionism had existed in the background, basking in the historical achievements of the painters of The New American, but without giving rise to a movement – perhaps the victim of the over-hyped claims that accompanied it.

Their legacy is undeniable. It is impossible to imagine the scale and ambition of contemporary art without them. So does abstract expressionism still have the power to move as it did in 1959? At a time when painting is vying for attention with other art forms, artists of the calibre of Tomescu demand attention, bringing their unrestrained energy and emotion to the fore in their authentic, highly gestural works and in my view, laying the foundation of a future art movement so sorely needed.

Jackson Pollock at work

[1] Lucy Stranger, Aida Tomescu, Artist Profile, August 2017

[2] Patrick McCaughey, Strange Country: Why Australian Painting Matters, Melbourne University Publishing, 2014

Main photo: Aida Tomescu, Artist Profile, August 2017

Andrew McIlroy is a visual artist, living and working in Melbourne, Australia

Comments